Remembering Cumberland

By Gary Stromberg

You could always tell when you were getting close to Cumberland Pool. On those lazy summer afternoons, you could hear the din of children yelling and shrieking. It was a calming kind of noise. The voices of young children all seemed to blend together.

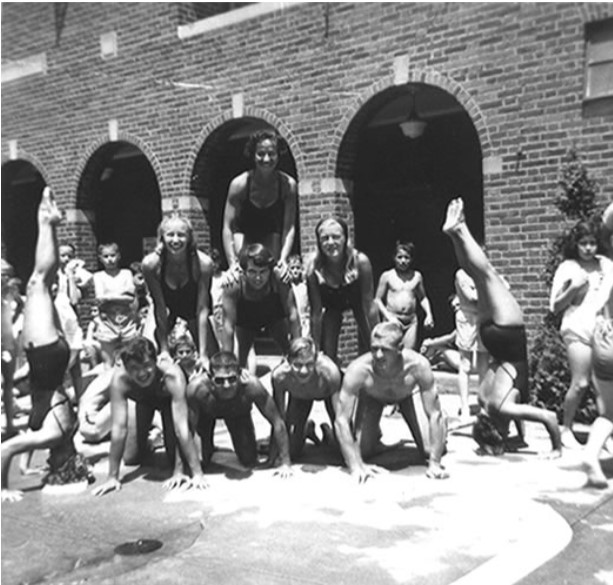

Cumberland Pool and Bathhouse, 1937

To get to the pool from my house on Woodward Avenue, I would walk east on Euclid Heights Boulevard. You could go all the way to Cumberland Road and take a left. Hardly anyone did that. There was a creek between Superior and Cumberland. Right next to the creek was a brick sidewalk. A shortcut to the pool. My sister Karin said that path was put in by the woman who owned the adjacent house. She felt sorry for the children who had to walk so far. She wanted to save them a few steps. I don’t know if that was true, or if it was just an urban legend.

Sometimes we would ride our bicycles to Cumberland. There was a fenced- in area that had a number of bicycle racks. I remember I had just bought one of those saddle bags that you strapped on to your bike. I had this great idea. When I locked my bike in that bike rack, I opened the saddle bag and I slipped the key behind a corner flap of the bag. That way I didn’t have to worry about losing the key inside the locker room. I figured no one would ever find the key tucked away behind that flap of the saddle bag. I was probably right. No one ever discovered that key. One afternoon I left the pool, headed to the bike rack and went to get the key out of the saddle bag. While I was in the pool someone had taken the saddle bag. They unknowingly took my key. I couldn’t unlock my bike. I was nine years old at the time. I remember just how upset I was. I was able to pull my bike out of the rack. I then lifted up the locked, back end of the bike. I struggled to wheel it all the way home on its front wheel.

It was a traumatic experience for me, but certainly not the most upsetting time at Cumberland Pool. I went swimming just about every summer day during those grade school years. You really couldn’t call it swimming. Basically, I would just stand in the water. Sometimes I would also walk in the water. I couldn’t swim a stroke. I kept saying to myself that maybe this was the year I would learn how to swim. I put it off, year after year. I finally took lessons when I was twelve years old.

While I was still in my walk-in-the-pool era, I went to Cumberland with a friend from the neighborhood named Kevin Clark. His brother Brian was also at the pool that day. Brian was five years older. He was much bigger than us and he started some rather intense horseplay. I don’t know if he picked up on the fact I couldn’t swim. He pounced on me and pulled me under the surface. He held me down for a few seconds. I was gasping for air when I jumped out of the water. My heart was pounding. I had never been under water that long. Brian Clark was not my favorite person after that. I would think about that incident every time I went by his house on Euclid Heights Boulevard. Brian joined the Marines after high school. He was sent to Vietnam. In October of 1966 I was in tenth grade. One morning, I went to the front porch and picked up the Plain Dealer. I read that Brian Clark was killed in Vietnam.

Cumberland Pool was a place where Cleveland Heights kids grew up. It was a place to socialize. A place to develop friendships. The teenagers who worked there were pretty tough enforcers. There were floating ropes that divided the shallow ends of the pool from the deeper middle section. The lifeguards who sat up in their elevated chairs, wearing zinc oxide on their nose, spent much of the day picking up a megaphone and admonishing swimmers to stop hanging on the floating ropes. All day long, you would hear these amplified voices blurting out, “Hey buddy, get off that rope. I am not sure what the big danger was. Those ropes were strung through those hard plastic floating cylinders. They could never sink. In my case, the lifeguards should have been yelling out, “Hey buddy, get on that rope.”

A bell would ring out when it was time for rest period. The kids at the pool knew when the bell rang, it was mandatory that they climbed out of the pool. Nonetheless, as the bell rang out, all of the lifeguards would still yell “Out, rest period. This would be followed by a loud groan from all of the young children. It was hot outside. We were having fun. We were swimming, diving or, in my case, just walking in the water.

The grownups and the lifeguards got a chance to swim during those rest periods. The lifeguards had it made. They had the best job in the pool. I know what the worst job was. I guess in the 1950s, there must have been an epidemic of athletes’ foot. It was rumored to be highly contagious. So after you changed into your swimsuit and took a shower, you had to march up to this raised platform. It was made out of wood and covered with a bath towel. Some guy would be sitting behind the platform. You were supposed to put your towel around your neck and then lift a foot onto the platform. When the tootsie inspector was ready, you were supposed to separate your toes, one at a time, so he could see if you were a carrier of that dreaded athletes’ foot. After you got the all-clear on the first foot, then you had to lift the up the other one and have that pass inspection. I guess it was possible to have athletes’ foot on one foot and not the other. Otherwise the malady would be called athletes’ feet.

Lifeguards at Cumberland Pool making a human pyramid, 1935

I don’t know if the tootsie inspectors actually ever discovered a violator. If they did, they probably would have called a lifeguard over and had him scream into his megaphone, “Hey buddy, get out of the bathhouse. Imagine the shame. The disgrace. The kid with athletes’ foot—or, God forbid, athletes’ feet, would be banished to the parking lot. Peering into the pool through the chain link fence. Bored out of his mind. Nothing to do but wander into the bike rack area and steal saddle bags from pathetic children.

Besides keeping kids off the ropes, and filling up athletes’ foot wards in area hospitals, pool workers had one other mission. If they noticed any child running on the pool deck, they would level a barrage of sarcasm at him. My favorite was “Hey buddy, where’s the fire?”

What is amazing to me is the fact that all of these same rule breakers were at Cumberland almost every day. The lifeguards and toe-checkers never bothered to learn any of our names. It was always “Hey buddy, this,” or “Hey buddy, that.”

They had three diving boards at Cumberland, Two low boards and one high board. Since I wasn’t exactly a member of the Olympic Swimming Team, I didn’t much bother with any of them. Most of the kids who went on the high board were show-offs. They thought they were cool. Why couldn’t they just walk in the water like all of the rest of us?