Forest Hill Park

A.D. Taylor, the landscape architect who designed Forest Hill Park, said that “one seldom finds an area of such size possessing such a diversity of topography, abundance of existing vegetation and many other natural advantages, located within a metropolitan area of a large city.” It is not an exaggeration to call Forest Hill Park one of the finest urban oases in the United States today.

The recent history of Forest Hill Park begins in 1853 when 13-year old John D. Rockefeller moved to Cleveland, OH, from western New York. By 1870, when Rockefeller organized the Standard Oil Company, Cleveland was an industrial giant among American cities. Dozens of railroads, steel mills, oil refineries, breweries and other industrial enterprises generated enormous wealth, soot and smoke. Recent immigrants from overseas and from America’s farms lived in hovels all over the city. Business owners built mansions on the famous Millionaires’ Row, an old Indian Trail now called Euclid Avenue. The Rockefeller mansion was a prominent addition to the row.

In 1873, Rockefeller purchased 109 acres of rural land east of Cleveland’s clutter and smoke. The front of the property was along Euclid Ave. in East Cleveland and extended into the city of Cleveland Heights. In 1913 Rockefeller purchased another 100 acres and a few years later, other small parcels were added to the estate, bringing the total property to 267 acres.

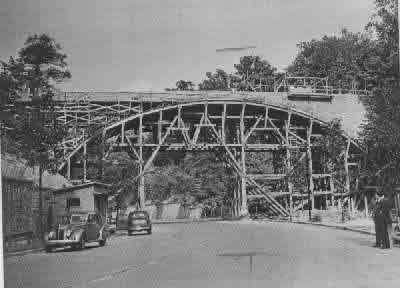

Construction of the bridge over (newly constructed and mis-named) Forest Hills Boulevard, 1936.

Rockefeller sold his original parcel in 1877 to the Euclid Avenue Forest Hill Association for a commercial sanitarium. The sanitarium was located at a prime location atop a hill with a view of Lake Erie. However, the project failed and in 1879 Rockefeller regained ownership. In 1880, the sanitarium became a private club for Rockefeller and his cronies, but it lasted only one year and the building was remodeled into a summer home for the Rockefellers. They named the house Homestead and used it from June until mid-September every year (even after they moved to New York in 1884) until 1915 when Mrs. Rockefeller died. In 1917 Homestead burned to the ground.

While John D. Rockefeller’s business practices were criticized by many, few would argue with his treatment of the estate that came to be called Forest Hill. He created carriage paths following the contours of the land and even made them longer than they needed to be so they would emerge at the most spectacular spot on the property. He built beautiful stone bridges over ravines using stone quarried on the property. An attractive nine-hole golf course was laid out on a plateau and bridal paths were built so he could race his horses. Two lakes were constructed. While maintaining most of the original trees, he also added others in strategic locations.

John D. Rockefeller, Jr., participated with his father in creating the major features of the estate and was given management control of the property at a young age. It is here that the son learned from the father to appreciate the outdoors and natural beauty; to recognize the necessity of open spaces for recreation and renewal; and most of all, the need to conserve such places. These lessons resulted in John Jr.’s gift’s to the American people of land with extraordinary natural and historical significance, including Acadia National Park in Maine, the Cloisters in New York City and Grand Teton National Park in Wyoming.

In 1923, Rockefeller left the disposition of the estate to his son, selling him all his real estate holdings in Cleveland, East Cleveland, and Cleveland Heights for $2.8 million. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., gradually gave or sold portions of Forest Hill to provide sites for Huron Road Hospital, Kirk Junior High School, and a Masonic hall, and to provide for the widening of existing streets bordering the estate. In the late 1920s, Rockefeller undertook the development of a model housing project on the portion of the estate east of Lee Boulevard. Eighty-one French Norman-style houses and a business block (all of which now are on the National Register) were built before the onset of the Depression and the collapse of the real estate market. In 1936, Terrace Road was extended through a portion of the properly abutting Euclid Avenue, and Forest Hill Boulevard (erroneously titled on street signs and maps, “Forest Hills Boulevard”) was developed through a ravine on the property, dividing what had once been the heart of the estate into two parts.

In 1938, conditions were right for John Jr. to dispose of the estate. The cities of East Cleveland and Cleveland Heights, where the Forest Hill Estate was located, were almost completely developed. East Cleveland was very densely populated, with little public open space. In addition, the federal government was struggling to alleviate the effects the nation’s economic collapse by providing employment for projects that benefited the public. The Works Progress Administration is one of the best known of the programs.

Rockefeller responded by giving to the cities of East Cleveland and Cleveland Heights 235 acres that is to forever be parkland. East Cleveland received about two-thirds of the land and Cleveland Heights the remainder. Rockefeller also gave the cities a plan for the development of the park by noted Cleveland landscape architect Albert Davis (A.D.) Taylor. Taylor was the president of the American Society of Landscape Architects and a protégé of the Olmstead firm of landscape architects founded by Frederick Law Olmstead, the father of American Landscape Architecture. He and Calvert Vaux designed Central Park in New York City and Olmstead himself designed many other significant parks across the United States.

Using labor paid for mainly by funds from the Works Progress Administration, East Cleveland and Cleveland Heights proceeded to develop the estate into a public park according to the Taylor plan. It included forested, secluded areas; lovely open vistas; and active recreational areas, mostly on the perimeter of the park. A decision that was, at the time, radical excluded automobiles from the inside of the park. Lawn bowling was popular, so two lawn bowling greens and a pavilion were included in the plan. Tennis courts, baseball fields, picnic facilities, comfort stations, trails (mostly following those laid out by Rockefeller), a boat house and lagoon and many other features were part of the design.

Rear view of the Rockefeller gatehouse. Homes lining Euclid Avenue are visible in the background. Photo courtesy of the Rockefeller Archives.

The scope of the effort to develop the park is difficult to appreciate today when much of it looks as though it’s in a natural state. In fact, some of it is in original condition. But, in one year alone (1939) 1,000 people were employed to create just part of the East Cleveland portion of the park. Work was begun on the Dugway Brook culvert and construction of the footbridge across Forest Hills Boulevard. Storm sewers were built, land graded and buildings started. By the time the war broke out in 1941, 13,000 shrubs and another 13,000 small trees had been planted and the existing A. D. Taylor plan structures were virtually complete.

Although Taylor was involved in the park until his death in 1951, not all his plans for Forest Hill Park came to fruition. A swimming pool, picnic areas, a lawn bowling green, an overlook and several other features did not materialize. The Superior Road side of the park was somewhat neglected, but plans for its development were finally approved in 1946.