The Struggle for Fair Housing: The St. Ann Audit

By Sven H. Dubie (ca. 2008)

Only in the 1960s did the United States begin seriously coming to terms with some of its institutionalized racial inequities. As part of this process, Congress passed several pieces of landmark legislation designed to eliminate racial discrimination in key areas of daily life, including access to public accommodations, employment, education and voting. One such law, the Civil Rights Act of 1968—commonly known as the Fair Housing Act—specifically banned discrimination based on race and several other categories with respect to the sale, rental, or financing of a home.

The City of Cleveland Heights is not often thought of as a proving ground for civil rights reform. In fact, in the early decades of the 20th Century, racially biased deed restrictions were fairly common in Cleveland Heights. And it is only in the last 20-30 years that the community has come to pride itself on being open and welcoming to people of all colors, countries and creeds. The passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968 provided an opportunity to examine the extent to which citizens of Cleveland Heights were genuinely committed to the idea of open housing. The driving force was inauspicious: As more and more prospective minority homeowners sought to buy properties in suburban Cleveland in the 1960s and 1970s, rumors abounded that they were being steered toward certain communities and away from others. In 1972, to investigate these allegations and ensure compliance with the Fair Housing Act, the St. Ann Catholic Church in Cleveland Heights sponsored what came to be known as the St. Ann Audit of Real Estate Practices. Charged with the task of systematically examining and documenting the experiences of minority homebuyers in Cleveland Heights, the St. Ann Audit would prove to be one of the most important, if at times unsettling, exercises in social justice in the history of our community.

Volatile Roots

The St. Ann Audit occurred against a backdrop of striking racial transformation in large metropolitan communities like Cleveland. Through the early part of the twentieth century, the black population in most northern cities was relatively small, and it was even more limited in emerging suburbs like Cleveland Heights. However, that began to change when thousands of blacks left the South, seeking greater economic opportunity and a less oppressive racial environment in the industrial centers of the North. Never before, and never again, were employment opportunities as extensive—sparked primarily by the blossoming of the auto industry and the highly restrictive immigration laws that characterized the 1920s. As black families became more prosperous during the economic boom of the 1940s and 1950s, they, like many urban whites, migrated out of Cleveland to communities on the city’s eastern periphery like East Cleveland, Cleveland Heights and Shaker Heights. Here they could aspire to own their own homes, have a bit of property and send their children to excellent and less crowded schools.

Still, as late as 1960, African-Americans constituted only one percent of the population of Cleveland Heights. However, as more and more blacks sought to establish residences in the community, more than a few people sought to halt the racial transformation. Over the course of the 1960s, there was a series of violent incidents designed to intimidate new and prospective black residents. Vandals attacked several properties occupied by blacks; there were bombings of black-owned homes and businesses that caused substantial damage (but, fortunately, no loss of life); and there was at least one shooting that was clearly racially motivated. As disturbing as these incidents were, it was some of the more subtle practices designed to promote residential re-segregation, as well as lessons drawn from the dramatic transformation of neighboring East Cleveland, that ultimately prompted the St. Ann’s Audit.

In 1967 this home on East Overlook, owned by J. Newton Hill, was bombed. (Cleveland Press Collection)

East Cleveland in the 1960s experienced an influx of black residents looking to avail themselves of the many assets the city had to offer. The racial transition of the city occurred rapidly as unscrupulous real estate agents employed practices such as steering, red-lining and block-busting to capitalize on racial fears. East Cleveland, already buffeted by a decline in manufacturing, experienced a precipitous drop in the value of its homes as panicked white residents were induced to sell well below market value. Properties were then sold to less affluent black buyers at inflated rates or divided up into multifamily units, often owned by absentee landlords. These factors combined to undermine the quality of housing stock and intensify the exodus of whites.

East Cleveland in the 1960s experienced an influx of black residents looking to avail themselves of the many assets the city had to offer. The racial transition of the city occurred rapidly as unscrupulous real estate agents employed practices such as steering, red-lining and block-busting to capitalize on racial fears. East Cleveland, already buffeted by a decline in manufacturing, experienced a precipitous drop in the value of its homes as panicked white residents were induced to sell well below market value. Properties were then sold to less affluent black buyers at inflated rates or divided up into multifamily units, often owned by absentee landlords. These factors combined to undermine the quality of housing stock and intensify the exodus of whites.

Aggressive Action

Determined to prevent what had occurred in East Cleveland from happening in their community, citizens in Cleveland Heights mobilized to face the challenges of integration. As early as 1964, a grassroots organization called Heights Citizens for Human Rights was formed to promote racial justice and the peaceful integration of the community. Two separate initiatives then were launched in the early 1970s, both of which sought to promote non-discrimination in housing. The first of these was a series of meetings by prominent religious leaders held at the Carmelite Monastery. The “Carmelite Group,” as the participants came to be known, provided a forum for addressing problems related to race relations and for developing a means to promote interracial harmony in Cleveland Heights. It was from this group that the vital organization known as the Heights Community Congress would be formed.

The second undertaking was started in response to an ongoing initiative within the Cleveland Catholic Diocese known as “Action for a Change,” sponsored by the Commission on Catholic Community Action. Action for a Change amounted to an intensive seminar on contemporary social justice issues and was designed to nurture in its participants a passion and commitment to advance the cause of social justice. Individuals were charged with identifying an area of social injustice in their community and taking concrete steps to address the problem. Accordingly, a group of five women parishioners—working mothers and homemakers—took it upon themselves to address the problem of housing discrimination in the Heights. Under the auspices of the St. Ann Parish in Cleveland Heights, these women formed the St. Ann Social Action Housing Committee—better known simply as the St. Ann Committee—in 1971.

Led by Suzanne Nigro, these women were drawn to this issue not simply because they were aware of the hostility that some black Americans were forced to endure when they tried to establish residency in Cleveland Heights, but because several of them had experienced first-hand the practice of real estate steering. As Nigro would later recall, upon arriving here in the early 1960s she and her husband were subtly discouraged by their real estate agent from considering purchasing a home in the Heights. Instead, they were directed toward properties in other communities. However, because the methods of steering and other manifestations of discrimination in the real estate industry were not overt or readily apparent, the central challenge of the St. Ann’s Committee would be to prove that, in fact, discriminatory practices did exist.

After looking at how other communities were responding to allegations of housing discrimination and monitoring compliance with the Fair Housing Act, the Committee learned that some cities were experimenting with a new practice that involved conducting “undercover” audits of real estate practices to determine whether there was discrimination. As it turned out, one such audit was underway in nearby Akron, Ohio. In this scenario, prospective renters (one black couple and one white couple) known informally as “checkers,” made separate inquiries about renting the same piece of property. The backgrounds of the checkers were virtually identical in every respect except race, so the logical inference one could make was that any difference in the treatment they received must be the result of racial discrimination. Inspired by this model, the St. Ann’s Committee developed a plan to conduct a similar audit of real estate practices in Cleveland Heights. In the spring and summer of 1972, what came to be known as the St. Ann Audit was undertaken. Like the Akron audit, it called for numerous pairs of black and white checkers with similar backgrounds and interests to make inquiries about property listings with the approximately ten real estate companies active at that point in the city. When the audits were complete, the collected data were compiled in a report set to be released in early September 1972. The controversial findings of the St. Ann Audit Report sent shock waves through Cleveland Heights and the reverberations from the report are still in evidence to this day.

Responses to the Audit

The findings of the audit, released in the late summer of 1972, proved deeply troubling to a community that prided itself on its openness and diversity, forcing business and civic leaders, as well as private citizens, to reexamine their own racial attitudes and to address more squarely the insidious nature of housing discrimination. It was unsettling and difficult work, but the civic response that transpired over the ensuing months and years stands as model of grassroots self-evaluation and reform of which our community can be rightfully proud.

When all the data from the St. Ann Audit were gathered, they revealed clear racial bias and discriminatory practices in the real estate business in Cleveland Heights. Indeed, instances of discrimination were documented at each of the ten companies covered by the audit. Additionally, the audit found that “steering” (i.e., using race to direct clients toward or away from particular communities) was commonly practiced by seven of the ten companies, confirming Nigro’s own experiences when she was discouraged from looking at properties in the Heights in the 1960s. The audit further revealed that white and black clients received very different treatment from realtors. For instance, a white client was much more likely to get a call back from a realtor than a black client; whites were usually shown a wider range of homes; and whites were taken on as clients much more quickly than were their black counterparts. In sum, not only did it appear the letter of the law set forth in the federal Fair Housing Act of 1968 was being violated in the Heights, but the spirit of the law was being thwarted as well.

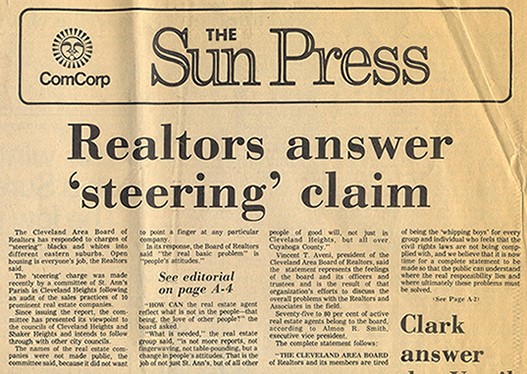

Reports on the audit’s findings were prominently featured in both the Sun Press and the Cleveland Plain Dealer in September 1972, and the revelations rocked the community. Many in the Heights were dismayed by the reports of pervasive discrimination and, as the St. Ann Committee hoped, residents saw the audit as a call to action. Others however, particularly in the real estate industry, were angered by the findings and felt they had been blindsided by the study. Indeed, some accused the Social Action Housing Committee of being nothing more than a cabal of troublemaking housewives.

Sun Press, October 12, 1972

City government in Cleveland Heights acknowledged the significance of the findings of the St. Ann Committee, but obviously was embarrassed by the evidence of widespread housing discrimination in a city that touted itself as welcoming people of all races. Nevertheless, it would take several years before the City developed and implemented a plan to address the housing situation.

Making Reform Happen

It was not the nature of those on the St. Ann Committee simply to spotlight a problem and leave others to grapple with solutions. Rather, the Committee, anticipating a sharp reaction to its audit and desiring to work constructively toward the resolution of serious social and political problems, developed a set of specific proposals to address the problems their report exposed. Toward this end it made a series of recommendations, including that the government of Cleveland Heights:

a. Take a proactive role in addressing the issue of housing discrimination and promote compliance with all federal, state, and local fair housing laws.

b. Enact and enforce legislation prohibiting the practice of steering.

c. Strengthen its housing department to help enforce laws and identify instances of discrimination.

d. Help develop educational programs to promote positive attitudes about integration.

Central to the implementation of these recommendations was the concurrent establishment of the Heights Community Congress (HCC), a private interfaith initiative begun in late 1972 by leaders of local Catholic, Jewish and Protestant congregations, and held at the Carmelite Monastery. These sessions led to the creation of the Heights Interfaith Council, whose purpose was to promote interdenominational social action across a range of issues, but especially with respect to racial integration. As reaction to the St. Ann Audit spread, the Interfaith Council sought specifically to create an organization to promote open housing, leading to the formal organization of the HCC in early 1973. This marked a milestone in the struggle for social justice in Cleveland Heights, as there is perhaps no organization that has played a greater role in promoting equal access to housing and racial integration in the Heights than the HCC.

That the initial mission of the HCC was to promote open housing in the Heights was made evident by virtue of its sponsorship of the Heights Housing Service, an agency tasked with sustaining the audit work of the St. Ann Committee and funded by the City of Cleveland Heights. Appropriately, Sue Nigro, the driving force behind the St. Ann Audit, was named director of the Housing Service. Nigro oversaw an extensive network of volunteers covering virtually every street in the city. Their mission was to monitor real estate activity in their immediate neighborhood to help ensure that discrimination did not occur. In light of the collaborative efforts of the City and grassroots organizations such as HCC, Cleveland Heights was twice named an All-American City for its creative and constructive efforts to address serious issues impacting the community.

That the initial mission of the HCC was to promote open housing in the Heights was made evident by virtue of its sponsorship of the Heights Housing Service, an agency tasked with sustaining the audit work of the St. Ann Committee and funded by the City of Cleveland Heights. Appropriately, Sue Nigro, the driving force behind the St. Ann Audit, was named director of the Housing Service. Nigro oversaw an extensive network of volunteers covering virtually every street in the city. Their mission was to monitor real estate activity in their immediate neighborhood to help ensure that discrimination did not occur. In light of the collaborative efforts of the City and grassroots organizations such as HCC, Cleveland Heights was twice named an All-American City for its creative and constructive efforts to address serious issues impacting the community.